ABSTRACT

Maternal satisfaction is a means of evaluating quality of maternal health care given in health facilities. The objective was to assess the level of maternal satisfaction and associated factors at Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital. Cross-sectional study was conducted on 420 clients by systematic sampling method from February 8, 2017 to September 25, 2017. Structured questionnaire that was prepared by Ethiopian Federal Ministry of Health was used. Pre-testing was done prior to the actual data collection process on a sample of 20 respondents and modified accordingly. The study was approved by Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital Senior Management Committee. The collected data were checked for completeness and consistency before being coded, entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 16. Logistic regression was used to assess the presence of association between dependent and independent variables using SPSS at 95% confidence interval (CI) and 5% margin of error. The study revealed that level of satisfaction among delivering mothers was 88%. Educational level (AOR=2.15, 95% CI=[1.02-3.71]), access to ambulance service (AOR=3.15, 95% CI=[1.02-3.78]), respectful delivery service (AOR=6.85, 95% CI=[4.35-6.95]), welcoming hospital environment (AOR=3.09, 95%CI=[2.30-2.69]), proper labor pain management (AOR=4.51, 95% CI=[3.12-5.01]) and listening to their questions (AOR=3.95, 95% CI=[2.35-4.36]) were independent predictors for maternal satisfaction. Even though most of the participants were satisfied, they still had unmet needs and expectations in the delivery service provider. The identified main determinants were level of education, access to ambulance service, welcoming hospital environment, proper pain management and listening to their questions. Therefore, there is need to improve the care given to maternity and appropriate strategy should be designed to address the unmet needs of mothers delivered in the hospital.

Key words: Maternal satisfaction, associated factors, delivery, West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia.

Globally, about 800 women die from pregnancy or labor related complications around the world every day. Two hundred and eighty-seven thousand women died during pregnancy and childbirth in 2010; more than half of these deaths occur in Africa. The ratio of maternal mortality in the Sub-Saharan Africa region is one of the highest, reaching 686 per 100,000 live births (Bongaarts, 2016). In Ethiopia, according to 2016 Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS), the estimated maternal mortality ratio was found to be 412 per 100,000 live births (World Health Organization, 2013). The existence of maternal health service alone does not guarantee their use by women (Ethiopian DHS, 2016). The World Health Organization promotes skilled attendance at every birth to reduce maternal mortality and recommends that women’s satisfaction be assessed to improve the quality and effectiveness of health care (World Health Organization (WHO) 2004). Client satisfaction is a subjective and dynamic perception of the extent to which the expected health care is received (Larrabee and Bolden, 2001). It is not important whether the patient is right or wrong, but what is important is how the patient feels (Jatulis et al., 1997). Studies done in Dhaka, Bangladesh, and South Australia showed that the level of maternal satisfaction with delivery care was 92.3 and 86.1%, respectively (Hasan et al., 2007; Australian Government, 2007). However, the level of satisfaction among laboring mothers in African countries is not enough; only 51.9 and 56% of mothers were satisfied with delivery services in South Africa and Kenya, respectively (Lumadi and Buch, 2011; Eva and Michael, 2009). Ethiopian studies done in Amhara Referral Hospitals and Assela Hospital revealed 61.9 and 80.7% satisfaction of mothers on delivery services, respectively (MesfinTafa, 2014; Tayelgn et al., 2011). Satisfaction with delivery service is a multidimensional construct embracing satisfaction with self (personal control), and with the physical environment of delivery ward and quality of care (Mehata et al., 2017).

The mother’s satisfaction during the birthing process is the most frequently reported indicators in the evaluation of the quality of maternity services (Goodman et al., 2004). Dimensions of care that may influence client satisfaction includes: Health care provider client interaction, service provision, physical environment, access, bureaucracy and attention to psychosocial problems. Many factors influence women’s satisfaction during delivery: certain demographic characteristics have been predominantly studied in relation to satisfaction during delivery services. For example, a study done in Sweden (n=2762) reported that younger women had more negative expectations related to childbirth and they experienced more pain and lack of control during labour compared with older women (Sawyer et al., 2013), while another study done in Brazil (n=15,688) showed no age related difference in women’s satisfaction with childbirth services (Bitew et al., 2015). Studies from developing countries show that satisfaction with services had a negative association with the amount of time women spent at the health facility before childbirth (Geerts et al., 2017). The educational level of women in different studies and settings has demonstrated positive, negative or nil association with satisfaction during delivery services (Srivastava et al., 2015; Haile, 2017). Other identified factors that influenced satisfaction with childbirth servicesare: having clean and orderly labour rooms and women-friendly delivery processes, such as having been prepared in advance for what to expect during the labour/postpartum/breast feeding period; involvement in the decision-making process; having a birth plan and being able to follow it; having pain relief during labour; having a birth companion and respectful care providers; receiving help from care providers in performing self and neonate’s care; and experiencing less symptoms in the postpartum period (Zasloff et al., 2008; D' Orsi et al., 2014; McKinnon et al., 2014; EChangee et al., 2015; Jafari et al., 2017).

A woman’s obstetric history, mode of delivery, and her feelings towards recent childbirth can also affect maternal satisfaction. For example, being multiparous, preferring a spontaneous vaginal delivery and being able to have a spontaneous vaginal birth (Karkee et al., 2014; McMahon et al., 2014) enhances the women’s satisfaction with giving birth. Qualitative studies on Indian women’s experiences and opinions on giving birth at a health facility reveal that they are not fully satisfied during delivery service, primarily due to the long waiting time before they meet a healthcare provider, having few opportunities to communicate with providers, not being involved in decision-making, and having stern care providers (Melese et al., 2014; Christiaens and Bracke, 2017; Camacho et al., 2012; Bhattacharyya et al., 2016; Ferrer et al., 2016). However, they settle for childbirth services perceived as ‘essential’ for safe childbirth rather than ‘desirable’ for a pleasant experience (Pal et al., 2010; Sabde, 2014; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2016; Hanefeld et al., 2017). While the community’s access to institutional delivery has improved, the assumption that accessibility is synonymous with quality of care, especially among policymakers, gives concern. This study aimed to assess women’s satisfaction with an institutional delivery service using a standardized scale with an intent to potentially use the findings in advocacy for service improvement. Studying the quality of institutional delivery service from client perspective will provide systematic information for service providers, decision makers, local planners and other stakeholders help understand to what extent the service is functioning according to clients’ perception, and what changes might be required to meet clients’ need as well as to increase utilization of the service by the target population. This study serves both knowledge generation and delivery service quality improvement purpose. The findings of this study can be used by local planners and decision makers to improve the quality of institutional delivery service.

Study design and period

Cross-sectional study was conducted at Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital, from February 8, 2017 to September 25, 2017.

Study area

Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital is found in Burecity administration 410 km away from Addis Ababa and 155 km away from Bahir Dar the capital city of Amhara regional state. The hospital primarily serves for four worked as: Bure, Bure city, Shindi and Sekela.

Population

Source population

All mothers delivered at Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital from February 8, 2017 to September 25, 2017.

Study population

Those systematically selected mothers who delivered at Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital from February 8, 2017 to September 25, 2017.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Mothers who delivered at Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital from February 8, 2017 to September 25, 2017 before discharge.

Exclusion criteria

Mothers who delivered at Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital and came for postnatal care were excluded to avoid recall bias.

Variables

The variables used for the study are dependent variable as satisfaction and independent variables as socio demographic characteristics of the respondents, interaction with healthcare provider, physical facilities, and service provision.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

Targeted groups of clients in this study were delivery attendants. The sample size was determined by using a single population proportion formula, which took the proportion of overall satisfaction at 65.2% (Jatulis et al., 1997), with a margin of error of 0.05 at the95% confidence interval (CI). Adding 10% non-response rate, the final sample size was calculated to be 420 patients. From the hospital pervious report about delivery, average number of clients who delivered in the hospital was 110 per month. Therefore the number of participants who visited the hospital was estimated for the study period; then sampling fraction for selecting the study participants was determined by dividing with the total estimated number of patients during the data collection period to the total sample size which was calculated to be two. The first study participant was selected by lottery method among the list from one to five; the next study participant was identified systematically in every two intervals until the required sample size was achieved.

Data collection procedure and quality assurance

A validated structured questionnaire prepared by the Ethiopian Ministry of Health to assess maternal satisfaction was used according to the objectives of the study and the local situation of the study area in Amharic language. The questionnaire was translated to English to assure consistency of the tool. Pre-testing was conducted on 20 respondents at Bure Health center delivery attendants.

Data management and data analysis

The collected data were checked for completeness and consistency before being coded, entered and analyzed using SPSS version 16. Summary statistics of sociodemographic variables were presented using frequency tables. Bi-variable analysis was done and variables with p-value less than 0.2 were included in the multiple variable analysis of logistic regression. The odds ratio and 95% confidence intervals were also computed at p-value of 0.05.

Ethical consideration

The research was approved by Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital Senior Management Committee. Permission to conduct the study was also obtained from Asrade Zewude Memorial Hospital maternity case team. During data collection, the purpose of the study was clearly explained to the participants, and informed oral consent was obtained. To ensure confidentiality and privacy no identity was linked to the questionnaire.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents

A total of 420 clients after delivery were involved in this study. As shown in Table 1, 60% of the respondents were between 15 and 24 years of age, 90% were married, 70% of the delivery was spontaneous, 70% of clients came to hospital by ambulance.

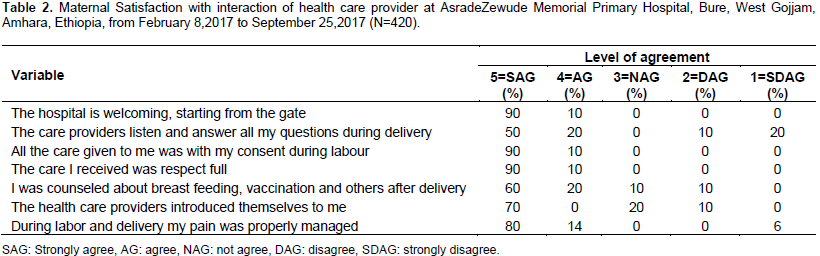

Health care provider-client interaction

The majority of participants (Table 2) agree and strongly agree to provider client interaction questionnaires.

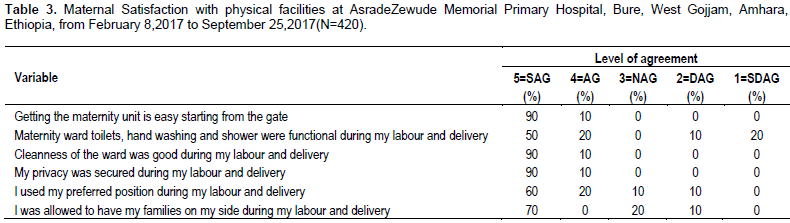

Maternal satisfaction with physical facilities

Only 50% strongly agreed and 20% agreed that there was a functional maternity ward toilet, hand washing and shower during their labour and delivery time (Table 3).

Maternal satisfaction with service provision

The majority of participants (60% strongly agreed and 40% agreed) responds positively to the questionnaire 'I have got a bed immediately' (Table 4).

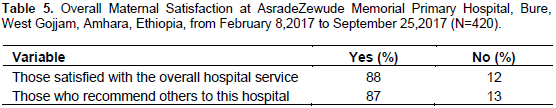

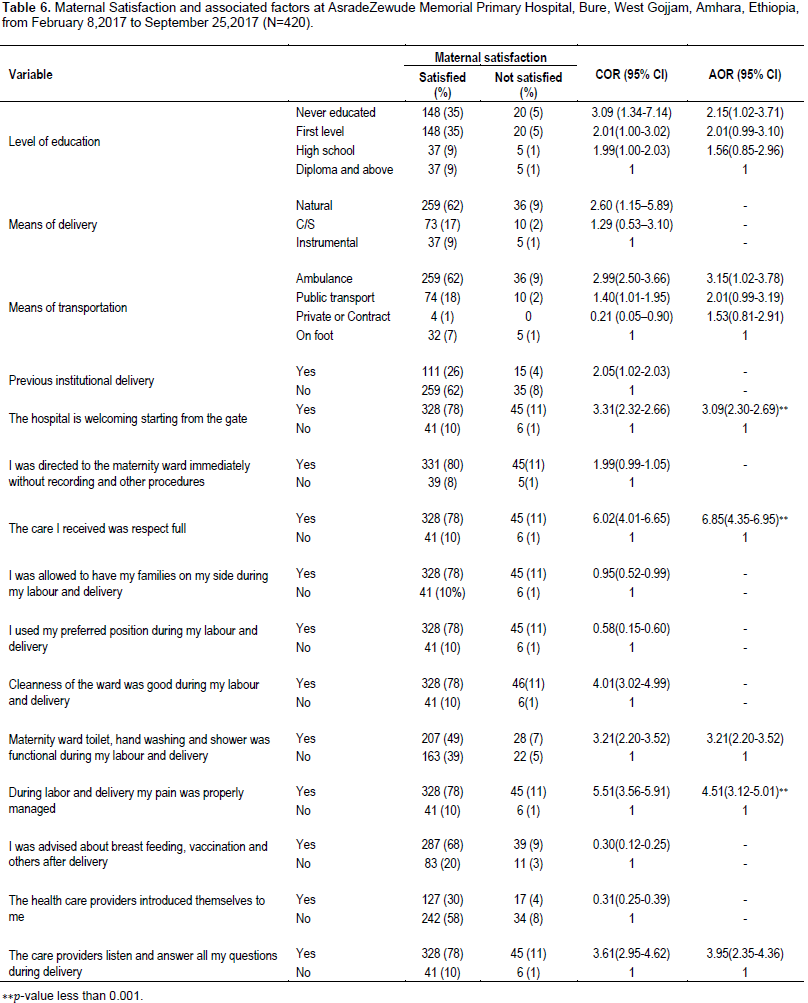

Overall satisfaction

Overall satisfaction was measured on 10 scales, 1 worst and 10 the best. Those who scored 6 and above was considered 'yes' for satisfaction. Their intention to recommend others to the hospital was measured using Yes (87%) and No (13%) options (Table 5). The regression output of factors for maternal satisfaction showed that mothers who think of the welcoming hospital environment was 3.09 (2.30 to 2.69) times more likely to satisfy than those who perceive the hospital environment was not welcoming (Table 6).

In this study, the overall satisfaction of mothers on delivery service was found to be 88%, which was comparable to the study conducted in Wolayita Zone (82.9%), Debremarkos town (81.7%) and Assela Hospital (80.7%) (Lumadi and Buch, 2011; MesfinTafa, 2014; Geerts et al., 2017). However, it was higher than the study, which was conducted in Jimma (77%) (Haile, 2017) and Amhara Referral Hospitals (61.9%) (Tayelgn et al., 2011) in Ethiopia and South Africa (51.9%) and Kenya (56%) in Africa (Lumadi and Buch, 2011; Eva and Michael, 2009). The difference with the above finding may be because of a real difference in the quality of services provided, expectation of mothers or the type of health facilities. Maternal educational status was significantly and inversely associated with their level of satisfaction with delivery services. Those respondents who were never educated were 2.15 more likely to satisfy with delivery service than whose educational level is diploma and above. This finding supports the study conducted in Assela Hospital and other foreign literatures. The literatures showed that clients had various expectations about hospital delivery that influenced their perception of care (MesfinTafa, 2014; Srivastava et al., 2015). This study revealed that those who came to the hospital by ambulance were 3.15 times more likely to satisfy than those who came on foot. This finding was related to accessibility as explained by other similar studies (Tayelgn et al., 2011; Bohren et al., 2015). Maternal level of satisfaction was also related to creating welcoming environment hospital to laboring mothers. Those clients who consider the hospital as welcoming environment were 3.09 times more likely to satisfy with maternal service. There was a strong association between maternal levels of satisfaction and respectful delivery care providers. Those participants who thought that care providers were respectful were 6.85 times more likely to satisfy with the delivery service. Perception of respondents of labor pain management was associated with level of maternal satisfaction. Those who answered yes were 4.51 times more likely to satisfy than those who answered no to proper labor pain management, according to their perception. Attention to laboring mother's concern was also related to the maternal level of satisfaction. Those who thought their questions and concerns were answered during labor were 3.61 times more likely to satisfy than those who thought not.

The aim of this study was to assess levels of maternal satisfaction and associated factors with delivery service at the Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital. The overall maternal satisfaction with the delivery service was found to be 88%. Even though the result was slightly higher than the previous studies conducted in Ethiopia, there are still unmet needs and expectations of mothers during labor and delivery that the hospital should focus on as delivery service quality improvement area. The identified associated factors were access to ambulance service, welcoming hospital environment, proper labor pain management, respectful care and listening to their questions.

Recommendation to Asrade Aewude Memorial Primary Hospital

The hospital shall better consider physical barriers to create a welcoming hospital environment for maternal service. The hospital should facilitate ambulance access for delivering mothers.

Recommendation to health care providers

The care providers should manage labour pain properly. When providing service, it should be with compassionate and respectful. The care provider should meet the social and psychological concerns of the delivering mothers.

The feelings associated with childbirth itself, due to limited opportunities of exploration in quantitative studies, pose some confounders like the ‘halo effect’ a positive attitude towards successfully given birth makes it difficult to separate childbirth satisfaction from satisfaction with childbirth services. Participants’ tendencies to rate services more positive in general is another known confounder. Participants’ subjectivity being pleased with services that are not necessarilly evidence based poses another confounder for quantitative studies measuring satisfaction.

The author has not declared any conflict of interests.

The author is extremely grateful to the women who gave their time in completing the questionnaires and Asrade Zewude Memorial Primary Hospital Senior Management for ethical approval of the study. This study was not funded by any agency, but the motivation came from Asrade Zewude Primary Hospital quality improvement unit as part of maternal service quality improvement.

REFERENCES

|

Australian Government (2007). Maternity Service in South Australia Public Hospital: Patient Satisfaction Survey Research, Australian Government, South Australia, Australia.

|

|

|

|

Bhattacharyya S, Srivastava A, Roy R, Avan BI (2016). Factors influencing women's preference for health facility deliveries in Jharkhand state, India: a cross sectional analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 16(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bitew K, Ayichiluhm M, Yimam K (2015). Maternal Satisfaction on Delivery Service and Its Associated Factors among Mothers Who Gave Birth in Public Health Facilities of DebreMarkos Town, Northwest Ethiopia. BioMed. Res. Int. pp. 1-6.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP (2015). The Mistreatment of Women during Childbirth in Health Facilities Globally: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Jewkes R, editor. PLOS Medicine [Internet]. Publ. Lib. Sci. 12(6):e1001847.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Bongaarts J (2016). WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group, and United Nations Population Division Trends in Maternal Mortality: 1990 to 2015 Geneva: World Health Organization, 2015. Popul. Dev. Rev. 42(4):726-726.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Camacho FT, Weisman CS, Anderson RT, Hillemeier MM, Schaefer EW, Paul IM (2012). Satisfaction with Maternal and Newborn Health Care Following Childbirth Measure. PsycTESTS Dataset [Internet]. Am. Psychol. Assoc. (APA)

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Changee F, Irajpour A, Simbar M (2015). Client satisfaction of maternity care in Lorestan province Iran. Iran J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 20:398-404.

|

|

|

|

Christiaens W, Bracke P (2007). Assessment of social psychological determinants of satisfaction with childbirth in a cross-national perspective. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 7(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

D' Orsi E, Brüggemann OM, Diniz CSG, Aguiar JM de, Gusman CR, Torres JA (2014). Desigualdadessociais e satisfação das mulheres com o atendimentoaoparto no Brasil: estudonacional de base hospitalar. Cadernos de SaúdePública [Internet]. FapUNIFESP (SciELO). 30(suppl 1):S154-S168.

|

|

|

|

Ethiopian DHS (2016).

View

|

|

|

|

Eva SB, Michael AK (2009). Women's satisfaction with delivery care in Nairobi's informal settlements. Int. J. Quality Health Care 21(2,1):79-86.

|

|

|

|

Ferrer BC, Jordana MC, Meseguer CB (2016). Comparative study analysing women'schildbirth satisfaction and obstetric outcomes across two dif-ferent models of maternity care Setting: 2univer-sity hospitals in south eastern Spain. Br. Med. J. 6:1-10.

|

|

|

|

Geerts CC, van Dillen J, Klomp T, Lagro-Janssen ALM, de Jonge A (2017). Satisfaction with caregivers during labour among low risk women in the Netherlands: the association with planned place of birth and transfer of care during labour. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 17(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Goodman P, Mackey MC, Tavakoli AS (2004). Factors related to childbirth satisfaction. Journal of Advanced Nursing [Internet]. Wiley-Blackwell. 46(2):212-219.

|

|

|

|

Haile TB (2017). Mothers' Satisfaction with Institutional Delivery Service in Public Health Facilities of Omo Nada District, Jimma Zone. Clin. Med. Res. 6(1):23.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hanefeld J, Powell-Jackson T, Balabanova D (2017).Understanding and measuring quality of care: dealing with complexity. Bull. World Health Organ. 95(5):368-374.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Hasan A, Chompikul J, Bhuiyan SU (2007). Patient Satisfaction with Maternal and Child Health Service among Mothers Attending the Maternal and Child Health Training in DahakaBangeladish, Mahidol University.

|

|

|

|

Jafari E, Mohebbi P, Mazloomzadeh S (2017). Factors Relatedto Women's Childbirth Satisfaction in Physiologic and Routine Childbirth Groups. Iran J. Nurs. Midwifery Res. 22:219-224.

|

|

|

|

Jatulis DE, Bundek NI, Legorreta AP (1997). Identifying Predictors of Satisfaction with Access to Medical Care and Quality of Care. Am. J. Med. Quality 12(1):11-17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Karkee R, Lee AH, Pokharel PK (2014). Women's perception of quality of maternity services: a longitudinal survey in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Larrabee JH, Bolden LV (2001). Defining Patient-Perceived Quality of Nursing Care. J. Nurs. Care Quality 16(1):34-60.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Lumadi TG, Buch E (2011). "Patients' satisfactionwithmidwifery services in a regional hospital and its referring clinics in the Limpopo Province of South Africa." Afr. J. Nurs. Midwifery 13(2):14-28.

|

|

|

|

McKinnon LC, Prosser SJ, Miller YD (2014). What women want: qualitative analysis of consumer evaluations of maternity care in Queensland, Australia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

McMahon SA, George AS, Chebet JJ, Mosha IH, Mpembeni RN, Winch PJ (2014). Experiences of and responses to disrespectful maternity care and abuse during childbirth; a qualitative study with women and men in Morogoro Region, Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 14(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Mehata S, Paudel YR, Dariang M, Aryal KK, Paudel S, Mehta R (2017). Factors determining satisfaction among facility-based maternity clients in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 25:17(1).

|

|

|

|

Melese T, Gebrehiwot Y, Bisetegne D, Habte D (2014). Assessment of client satisfaction in labor and delivery services at a maternity referral hospital in Ethiopia. Pan Afr. Med. J. Pan Afr. Med. J. p17.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

MesfinTafa RA (2014). Maternal Satisfaction with the Delivery Services in Assela Hospital, Arsi Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia, 2013. Gynecol. Obstetrics 4(12).

|

|

|

|

Mukhopadhyay S, Mukhopadhyay D, Mallik S, Nayak S, Biswas A, Biswas A (2016). A study on utilization of JananiSurakshaYojana and its association with institutional delivery in the state of West Bengal, India. Indian J. Publ. Health 60(2):118.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Pal R, Das P, Basu M, Tikadar T, Biswas G, Mridha P (2010). Client satisfaction on maternal and child health services in rural Bengal. Indian J. Community Med. 35(4):478.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sabde Y, De Costa A, Diwan V (2014). A spatial analysis to study access to emergency obstetric transport services under the public private "Janani Express Yojana" program in two districts of Madhya Pradesh, India. Reprod. Health 11(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Sawyer A, Ayers S, Abbott J, Gyte G, Rabe H, Duley L (2013). Measures of satisfaction with care during labour and birth: a comparative review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 8:13(1).

|

|

|

|

Srivastava A, Avan BI, Rajbangshi P, Bhattacharyya S (2015). Determinants of women's satisfaction with maternal health care: a review of literature from developing countries. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15(1).

Crossref

|

|

|

|

Tayelgn A, Zegeye DT, Kebede Y (2011). "Mothers'satisfaction with referral hospital delivery service in Amhara Region, Ethiopia." BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 11:78.

Crossref

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (WHO), (2004). Making Pregnancy Safer: The Critical Role of the Skilled Attendant: A Joint Statement by WHO, ICM, FIGO, World Health Organization (WHO), Geneva, Switzerland.

|

|

|

|

World Health Organization (2013). World Health Statistics 2013; A WealthofInformationonGlobalHealth, World Health Organi-zation, Geneva, Switzerland.

|

|

|

|

Zasloff E, Schytt E, Waldenström U (2008). First Time Mothersʼ Pregnancy and Birth Experiences Varying by Age. Obstetric Anesthesia Digest 28(2):76-77.

Crossref

|